|

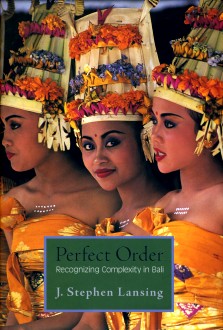

Perfect

order : recognizing complexity in Bali / J. Stephen Lansing. -

Princeton (NJ) : Princeton university press, 2006. -

XII-225 p. : ill. ; 23 cm. -

(Princeton studies in

complexity).

ISBN

0-691-02727-7

|

NOTE

DE L'ÉDITEUR

: Along rivers in Bali, small groups of farmers meet

regularly in water

temples to manage their irrigation systems. They have done so for a

thousand years. Over the centuries, water temple networks have expanded

to manage the ecology of rice terraces at the scale of whole

watersheds. Although each group focuses on its own problems, a global

solution nonetheless emerges that optimizes irrigation flows for

everyone. Did someone have to design Bali's water temple networks, or

could they have emerged from a self-organizing process ?

Perfect Order

— a groundbreaking work at the nexus of

conservation,

complexity theory, and anthropology — describes a

series of

fieldwork projects triggered by this question, ranging from the

archaeology of the water temples to their ecological functions and

their place in Balinese cosmology. Stephen Lansing shows that the

temple networks are fragile, vulnerable to the cross-currents produced

by competition among male descent groups. But the feminine rites of

water temples mirror the farmers' awareness that when they act in

unison, small miracles of order occur regularly, as the jewel-like

perfection of the rice terraces produces general prosperity. Much of

this is barely visible from within the horizons of Western social

theory.

The fruit of a decade of

multidisciplinary research, this absorbing

book shows that even as researchers probe the foundations of

cooperation in the water temple networks, the very existence of the

traditional farming techniques they represent is threatened by

large-scale development projects.

| ❙ |

J. Stephen Lansing is Professor in the Departments

of Anthropology and Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University

of Arizona, and Research Professor at the Santa Fe Institute. |

|

| EXCERPT |

|

The

transition from myth

to reason

remains a problem even for those who recognize that myth too contains

reason.

☐ Marcel Detienne, The

Masters of Truth in Archaic Greece

— cité en épigraphe |

The water

temples

of Bali went mostly unnoticed until the Green Revolution in

agricultural interfered with their role in the management of the rice

terrace ecology. But even after their functional role became apparent,

they proved to be difficult to comprehend from within the horizons of

Western social science. Water temple networks depend on unprecedented

levels of cooperation among farmers ; they actively manage the

ecology of the rice terraces at the scale of whole watersheds, and they

appear to be organized as dynamical networks. Moreover, a great deal of

what goes on in them falls into the Western category of

« religion » or even

« magic ». But from the

perspective of Balinese

farmers, these « magical » ideas

and practices

provide indispensible tools for governing the subaks 1,

the rice paddies, and their own inner worlds. Water temple rituals draw

on Hindu and Buddhist tradition of thought to create the preconditions

for a robust system of self-governance. The wedding of these ideas with

the managerial capacity of temple networks provides powerful tools for

communities to impose an imagined order on the world. However, the

farmers' recognition that such tools exist is coupled with an awareness

of the ease with which they can fail. A certain kind of self-mastery,

and awareness of interdependencies, is understood to be a prerequisite

for governing both the social and natural worlds. These Balinese ideas

about selfhood contrast with the celebration of the emergence of the

autonomous subject in Western social thought. (A darker vision, perhaps

most cogently expressed by the scholars of the Frankfurt School,

associates the triumph of the unitary subject with rise of totalitarian

rationality. But these two versions of the story of the emergence of

the subject, which seem to us so far apart, draw similar connections

between objective economic conditions and the subjective awareness of

individuals.) The world of the water temples, I suggest, has different

lessons to impart.

☐

Introduction,

pp. 18-19

| 1. |

Subaks

are egalitarian organizations that are empowered to manage the rice

terraces and irrigation systems on which the prosperity of the village

depends. — Introduction,

p. 5 |

|

|

| COMPLÉMENT

BIBLIOGRAPHIQUE |

- « Evil

in the morning of the world : phenomenological approaches to a

Balinese community », Ann Arbor : Center

for South and

Southeast Asian Studies, University of Michigan (Michigan Papers on

South and Southeast Asia, 6), 1974

- « The

three worlds of Bali », New York : Praeger,

1983

- « Priests

and programmers : technologies of power in the engineered

landscape of Bali », Princeton (NJ) :

Princeton

university press, 1991, 2007

- « The

Balinese », Fort Worth (Texas) : Harcourt

Brace college publishers, 1995

- «

Islands of order : a guide to complexity modeling for the

social sciences » with Murray P. Cox, Princeton (NJ) :

Princeton

university press, 2019

|

| J.

Stephen Lansing |

|

|

| mise-à-jour : 30 novembre 2021 |

|

|

|

|